A Stateless Object Isn’t an Object

I’ve come to the conclusion that most of us are misusing objects. In doing so, we’re missing the point of programming.

Object orientation has two parents. One was fairly strict; it saw the world in terms of types and abstractions. It viewed objects as being things constructed from classes, getting both their behavior and the shape of their state from the class that created them. Inheritance was used to share behaviour, often in ways that were convenient but baffling: if you had class Person that you wanted to add to a linked list, your make that class a subclass of Link. This parent was called Simula.

The other parent was more of a party animal. Smalltalk was all about the objects: each was effectively an independent process with its own state. The only way to access it was by sending it messages. Objects in Smalltalk were often long-lived (measured in years) bexcause they were permanent residents of something called the image. Everything was inspectable, and everything was open to change. It was an environment for doing things, not thinking about doing them.

It turns out that Simula had the stronger genes: C++, Ada, Java, Swift, and, to some extent, Ruby, all take the stance that classes are the backbone of OO programming.

It’s All About State

The trouble with classes is that they intimately couple state and the functions that manipulate that state. Indeed, this is often heralded as a benefit of the paradigm.

It isn’t.

Managing state is a vital part of programming. But it’s the boring and nonproductive part.

A program is something that transforms data. It takes inputs and produces outputs. It responds to events by changing some state.

Relying on objects makes it more difficult to do this: the coupling of functions and instance data means that every object has two conflicting personalities, one focussed on maintaining the integrity of the state and the other driven to change that state.

Make Transformations First Class

Let’s look an some typical OO code. Given an account number, it finds the correctonding customer, and from there finds the active accounts, and sums their balances.

balance = Customer

.find(account_number)

.active_accounts()

.sum_balance()This is bread and butter code. But it’s bad code.

The fault lies in the . operator. It invokes the method on its right in the context of the object on its left. When you use it, you have to make sure that the object has that method, and that it does the correct thing. Typically this means that we load our classes with a bunch of convenience methods just to provide the correct object mappings: Customer.find presumably returns a Customer object. The Customer class must then have an active_accounts instance method that returns a new object of class AccountCollection that in turn has an instance method sum_balance that returns a Currency object.

The . operator encourages us to fill our classes with convenience methods simply so that we can write code that reads well.

But let’s forget about that for a minute, and think of our problem not in terms of classes but instead in terms of transformations.

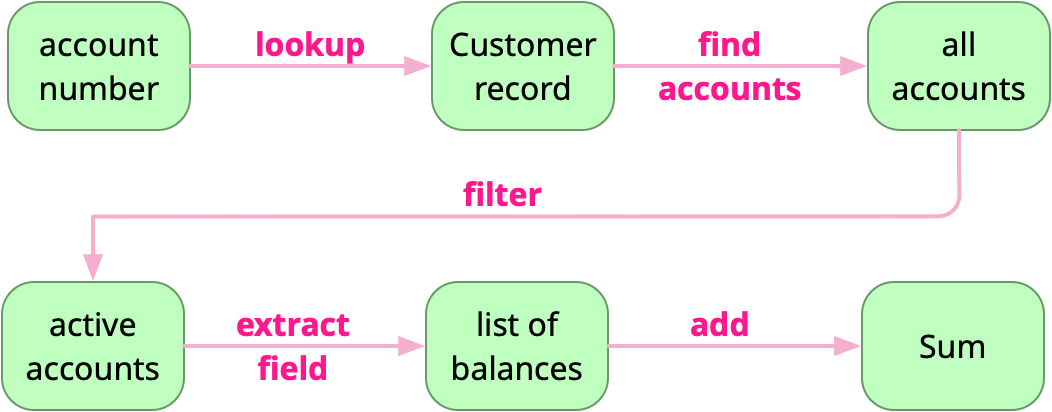

Now our problem looks more like this:

The boxes represent some part of the state, and the arrows are transformations applied to the state. The account number is transformed into a customer record, which is transformed into a list of accounts, and so on.

In many languages, this process can be expressed directly as a pipeline of operations. Elixir might look like this:

account_number

|> Customer.lookup

|> extract_customer_accounts

|> filter(&account_is_active/1)

|> extract_field(:balance)

|> sumIn this code there are no objects; instead we have data structures containing state, and each data structure is processed by a function to produce a new data structure. And, just as important, each of these data structures is immutable.

If you come from an OO background, you’re probably thinking that this is bullshit. It looks like more code, and possibly even lower-level code.

But stop and think about what this means. The functional part of your code is no longer tied to the data. And functions are now independent of each other: no function relies implicitly on the state tucked away in an instance variable by some prior function. Just think how this changes how you can approach testing. And composing code. And sharing. And…

So, Give Up Objects and Write Functional Code?

No. I personally use a middle ground, and it is working really well for me. I still write classes and use objects. By they are no longer the logic of my programs.

I use objects to hold state. The only methods they contain deal directly with setting and validating that state. They may also have a method to return their representation as a string or as JSON, and they might have a copy constructor (see later).

But these objects are immutable: they only reveal state via accessor methods, and they have no interface that changes their state.